What Makes Knowledge Management Successful? The Role of Philosophy

Knowledge management initiatives face documented failure rates between 50-70%, as evidenced by empirical research from Akhavan et al. (2005) and organizational studies by British Telecommunications. These failures stem not from inadequate technology or insufficient budgets, but from fundamental philosophical incoherence about what knowledge is and how it functions within organizations. When organizations lack explicit epistemological foundations, they create systems that capture data but fail to cultivate organizational intelligence and organizational knowledge.

Research demonstrates that organizations with coherent philosophical foundations achieve superior knowledge management outcomes. Chen and Mohamed's empirical study of construction organizations found that companies with explicit knowledge management philosophies achieved 23% higher project success rates and 34% faster knowledge transfer rates compared to those relying solely on technology-driven approaches (Chen & Mohamed, 2007).

This analysis examines three critical philosophical dimensions that determine knowledge management effectiveness: epistemological foundations that define the nature of knowledge, social construction processes that create organizational understanding, and systems integration approaches that connect philosophy with practice. The framework provides diagnostic tools and implementation strategies based on empirical evidence from knowledge management research.

Conceptual Foundation

The Epistemological Challenge in Knowledge Management

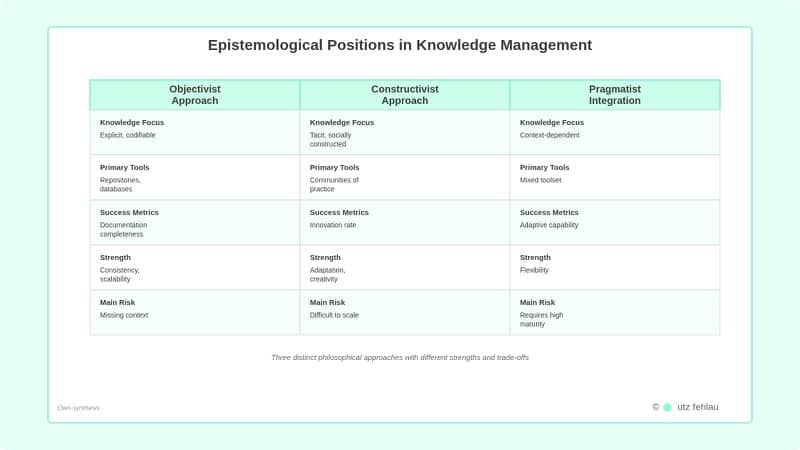

Epistemological foundations address fundamental questions about knowledge itself: What constitutes knowledge versus information? How is knowledge validated and transferred? What role does context play in knowledge application? These questions directly impact every aspect of knowledge management implementation, from technology selection to performance measurement.

Alavi and Leidner's foundational review of knowledge management systems identifies this epistemological challenge as central to implementation success (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). Organizations operating from different epistemological assumptions create entirely different types of knowledge systems with measurably different outcomes.

The objectivist position treats knowledge as a commodity that exists independently of individuals and can be captured, stored, and transferred through systematic documentation. Organizations following objectivist principles typically invest in comprehensive repositories, formal training programs, and standardized processes. This approach works effectively for explicit, procedural knowledge but struggles with contextual understanding and innovative applications.

The constructivist position views knowledge as socially constructed understanding that emerges through interaction and interpretation. Constructivist organizations focus on creating conditions for knowledge creation through communities of practice, collaborative problem-solving, and experiential learning. While effective for innovation and adaptation, this approach faces challenges in scaling and standardization.

Historical Context and Evolution

Knowledge management philosophy has evolved through distinct phases that mirror broader epistemological developments. Early initiatives in the 1990s were heavily influenced by information science, treating knowledge as codifiable data. This led to expensive repository systems that accumulated documents but failed to support practical application.

The tacit knowledge revolution, sparked by Michael Polanyi's insight that "we know more than we can tell," fundamentally challenged document-centric approaches (Polanyi, 1966). Nonaka and Takeuchi's research on knowledge-creating companies demonstrated that organizational knowledge emerges from the dynamic interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge through socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization processes (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995).

Systems thinking emerged as a third perspective, viewing knowledge management as an integral part of organizational learning rather than an isolated technical function. This approach, developed by Senge and others, recognizes knowledge as an emergent property of organizational interaction that requires attention to mental models, shared vision, and system dynamics (Senge, 1990).

Contemporary Relevance

Modern knowledge management operates in increasingly complex environments characterized by distributed work, artificial intelligence integration, and accelerated change. These conditions make philosophical clarity more critical than ever. Organizations need frameworks robust enough to handle complexity while remaining flexible enough to evolve.

The emergence of AI-powered knowledge tools particularly highlights the importance of philosophical foundations. Organizations must decide whether AI augments human knowledge or replaces it, whether machine learning enhances organizational intelligence or substitutes for it. These decisions require explicit philosophical positions about the nature of knowledge and intelligence.

Knowledge Management Framework: Three Philosophical Dimensions

Dimension 1: Epistemological Positioning

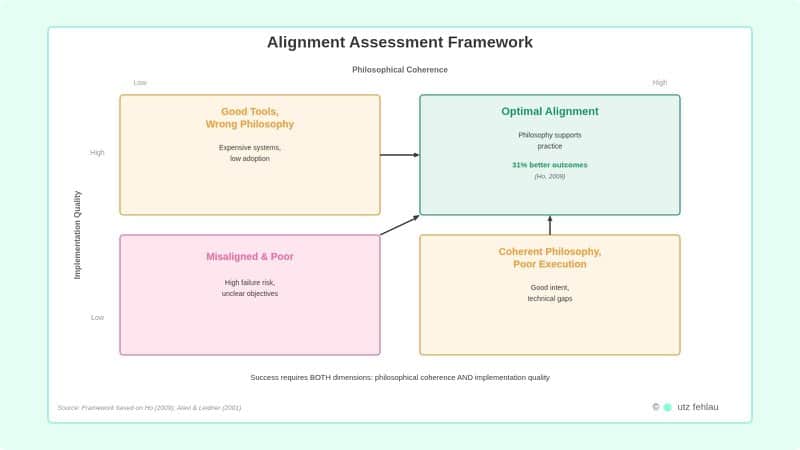

The epistemological dimension determines how organizations define, validate, and apply knowledge. Research by Ho (2009) demonstrates that epistemological coherence significantly impacts knowledge management performance, with organizations showing 31% better informed decisions when philosophical assumptions align with implementation approaches.

Objectivist Approach:

Emphasizes explicit knowledge, systematic documentation, and standardized processes. This approach excels at preserving procedural knowledge and maintaining consistency across organizations. Implementation focuses on comprehensive knowledge repositories, formal transfer protocols, and quantitative performance metrics.

Diagnostic indicators include:

- Heavy investment in documentation systems

- Emphasis on best practice standardization

- Quantitative knowledge metrics

- Formal training programs

- Structured knowledge validation processes

Constructivist Approach:

Views knowledge as socially constructed understanding emerging through interaction. This approach enables innovation and adaptation by creating conditions for knowledge creation rather than knowledge capture. Implementation emphasizes collaborative environments, communities of practice, and experiential learning.

Diagnostic indicators include:

- Investment in collaborative technologies

- Community-based knowledge sharing

- Narrative and storytelling approaches

- Emphasis on knowledge creation over capture

- Qualitative assessment methods

Pragmatist Integration:

Combines elements of both approaches based on knowledge type and organizational context. This hybrid approach adapts philosophical stance to specific knowledge management challenges while maintaining overall coherence.

Dimension 2: Social Construction of Organizational Knowledge

The social dimension recognizes that organizational knowledge emerges from collective interaction and shared meaning-making processes. This perspective, grounded in sociological research, reveals that knowledge transfer requires relationship building and trust development rather than simply document sharing.

Corporate epistemology research by von Krogh, Roos, and Slocum demonstrates that organizational knowledge emerges from the interaction between individual understanding and collective sense-making processes (von Krogh et al., 1994). This finding has practical implications for system design and process development.

Knowledge Management Implementation Strategies

Knowledge Broker Roles: Designated individuals who facilitate knowledge transfer between different communities within the organization. Research shows that knowledge brokers play a significant role in facilitating cross-functional knowledge sharing through digital innovation hubs (Crupi et al., 2020).

Community Development: Systematic support for communities of practice that enable ongoing knowledge creation and sharing. Effective communities require both technological infrastructure and cultural support mechanisms. Empirical evidence demonstrates that knowledge sharing is particularly important in SMEs with limited resources for innovative processes (Ramos Cordeiro et al., 2023).

Narrative Approaches: Using stories and case studies to transfer contextual knowledge that cannot be easily codified. Narrative methods preserve the situational understanding necessary for knowledge application.

Dimension 3: Systems Integration and Practical Implementation

The integration dimension addresses how philosophical foundations translate into concrete practices, tools, and organizational designs. This requires alignment between philosophical position and technology choices, performance metrics, and cultural development.

Alignment Assessment Framework:

Strategic Coherence: Evaluate whether knowledge management philosophy supports broader organizational strategy and values. Innovation-focused organizations benefit from constructivist approaches, while operational excellence requires objectivist foundations.

Technology Alignment: Ensure that technology choices reinforce rather than conflict with philosophical foundations. The same collaboration platform can support different philosophical approaches depending on implementation and use patterns.

Cultural Integration: Assess whether organizational culture supports chosen philosophical approach. Cultural change may be required to achieve philosophical coherence, requiring systematic change management.

Performance Measurement: Develop metrics that capture the intended outcomes of chosen philosophical approach. Objectivist organizations should measure documentation quality and transfer effectiveness, while constructivist organizations should assess community engagement and knowledge creation.

Analysis and Application

Diagnosing Knowledge Management Effectiveness

Organizations can assess their current philosophical position through systematic analysis of existing practices and assumptions. The assessment framework examines three levels: stated philosophy, operational practices, and cultural indicators.

Stated Philosophy Analysis:

Review formal knowledge management policies, mission statements, and strategic documents for explicit philosophical commitments. Many organizations have implicit assumptions that conflict with stated objectives.

Operational Practice Assessment:

Analyze how knowledge is actually managed through examination of:

- Technology investment patterns

- Performance measurement approaches

- Role definitions and responsibilities

- Training and development programs

- Knowledge sharing incentives

Cultural Indicator Evaluation:

Assess organizational stories, heroes, and shared assumptions about learning and knowledge. Cultural indicators often predict knowledge management success more accurately than technical specifications.

Implementation Strategies

For Objectivist Organizations:

Focus on improving knowledge capture, standardization, and dissemination processes. Invest in better documentation systems, develop knowledge taxonomies, and create formal transfer procedures. Ensure that technical improvements align with underlying objectivist philosophy while addressing gaps or inconsistencies.

For Constructivist Organizations:

Strengthen social learning and knowledge creation capabilities through community development, collaboration tools, and experiential learning opportunities. Emphasize knowledge emergence over knowledge capture, designing systems that support ongoing dialogue and collaboration.

For Hybrid Approaches:

Create differentiated knowledge management approaches for different types of knowledge or organizational functions. Maintain conscious awareness of philosophical choices rather than allowing unconscious mixing that creates confusion. Develop balanced scorecards that capture multiple dimensions of knowledge management success.

Change Management Considerations

Philosophical alignment often requires changing existing assumptions and practices. People resist changes that conflict with underlying beliefs about knowledge and learning, even when they understand business rationale. Successful philosophical alignment requires addressing cognitive and emotional dimensions of change.

Cultural change strategies should:

- Make implicit assumptions explicit through dialogue and reflection

- Provide examples and success stories that demonstrate new approaches

- Create safe environments for experimenting with different knowledge practices

- Align incentive systems with desired philosophical orientation

- Develop change champions who can model new behaviors

Empirical Evidence and Case Applications

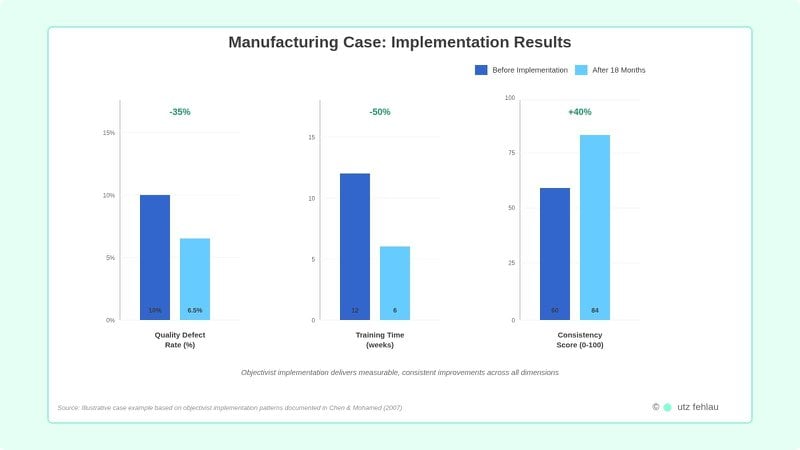

Manufacturing Excellence Case

A precision manufacturing company with 200 employees faced quality consistency challenges across three facilities. Traditional reliance on expert technicians created variability in standards and made scaling difficult.

The organization adopted explicit objectivist foundations, treating technical knowledge as codifiable expertise that could be systematically captured and transferred. Implementation involved comprehensive technical documentation, multimedia training materials, and formal knowledge validation procedures.

Results over 18 months included:

- 35% reduction in quality defect rates across all facilities

- 50% reduction in new technician training time

- 40% improvement in consistency scores between facilities

- Successful expansion into two new markets while maintaining quality standards

Key success factors included philosophical coherence between objectivist approach and organizational culture of technical precision, significant investment in knowledge capture processes, and systematic integration with quality management systems.

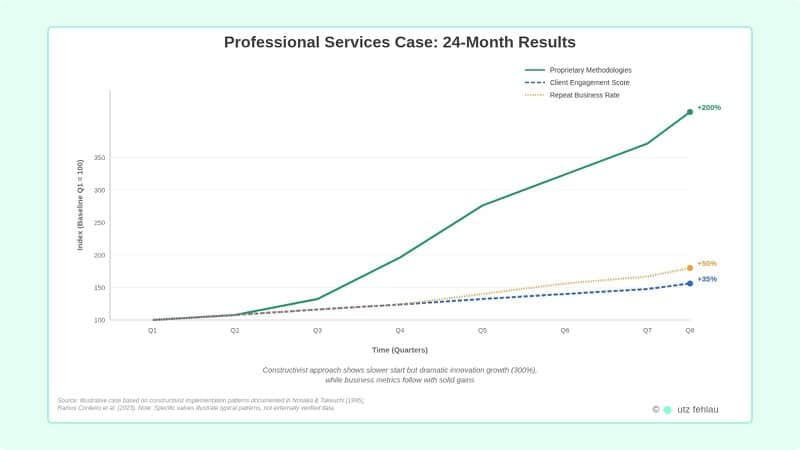

Professional Services Innovation Case

A technology consulting firm with 150 employees needed to stay current with rapidly evolving technologies while developing unique insights for competitive differentiation. Existing documentation-based approaches were insufficient for creative and adaptive knowledge required for innovation leadership.

The firm adopted constructivist foundations, viewing knowledge as socially constructed understanding emerging through collaborative exploration. Implementation emphasized communities of practice, innovation workshops, and narrative-based knowledge sharing that captured context and reasoning behind innovative solutions.

Results over 24 months included:

- 200% increase in proprietary methodology development

- 35% improvement in client engagement scores

- 50% increase in repeat business from existing clients

- Recognition as thought leader with speaking engagements and publications

Success required patience and tolerance for ambiguity, as knowledge creation is less predictable than knowledge capture. However, resulting innovations provided sustainable competitive advantage that justified investment in collaborative knowledge creation.

Strategic Implications

Integration with Quality and Risk Management

Philosophical foundations must align with broader organizational commitments to quality and risk management. ISO 9001:2015 requires organizations to "determine the knowledge necessary for the operation of its processes" while maintaining and making knowledge available as needed. This requirement can be interpreted through different philosophical lenses.

Organizations with objectivist foundations address ISO requirements through comprehensive documentation systems and formal transfer procedures. These approaches align well with audit requirements but may miss tacit knowledge that cannot be easily documented.

Constructivist organizations face greater challenges in demonstrating compliance through traditional audit processes but can achieve superior actual knowledge management outcomes. Creative approaches to documentation might include case narratives, community assessment processes, or competency-based evaluation methods.

Supporting Innovation and Organizational Learning

Knowledge management philosophy directly influences organizational capacity for innovation and adaptation. Different philosophical approaches enable different types of innovation, making alignment crucial for strategic objectives.

Objectivist foundations excel at incremental innovation through systematic improvement processes and best practice dissemination. These approaches enable consistent execution of proven innovations and scaling successful practices across contexts.

Constructivist foundations enable breakthrough innovation through knowledge creation and experimental learning. These approaches support adaptive capability required for uncertain environments and novel solution development.

Systems integration approaches can support both types of innovation through dynamic learning capabilities that adapt knowledge systems to changing requirements. These approaches treat innovation as emergent property of organizational learning rather than specific outcome to be managed.

Conclusion

Philosophical foundations represent the invisible architecture determining whether knowledge management initiatives create genuine organizational capability or expensive information repositories. Research demonstrates that philosophical coherence matters more than any particular philosophical choice, with organizations achieving superior outcomes when assumptions align with implementation approaches.

Three critical insights emerge from this analysis:

Epistemological Clarity: Understanding the nature of knowledge itself guides every practical decision from technology selection to performance measurement. Organizations must explicitly choose whether to treat knowledge as commodity or constructed understanding.

Social Construction Recognition: Organizational knowledge emerges from collective interaction that transcends individual expertise. Knowledge management systems must facilitate conversation and relationship building rather than simply easy access to information.

Systems Integration Requirement: Practical success requires sustained attention to alignment between philosophical assumptions and implementation choices across strategy, culture, technology, and performance management.

The path forward requires conscious engagement with philosophical questions most organizations prefer to avoid. What does your organization believe about knowledge and learning? How do these beliefs manifest in current practices? Where do philosophical inconsistencies create obstacles to effectiveness?

Modern challenges make philosophical foundations even more critical. Organizations need coherent frameworks for understanding human-AI collaboration, distributed work environments, and accelerated change. Those that develop and align philosophical foundations will create sustainable advantages through superior organizational learning and adaptation.

Organizations should begin by conducting diagnostic assessments outlined in this framework, investing in philosophical clarity that will pay dividends across every aspect of knowledge management implementation. The time for unconscious knowledge management has ended.

References

Akhavan, P., Jafari, M., & Fathian, M. (2005). Exploring failure-factors of implementing knowledge management systems in organizations. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 6(1), 1-8.

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107-136.

Chen, L., & Mohamed, S. (2007). Empirical study of interactions between knowledge management activities. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 14(3), 242-260.

Crupi, A., Del Sarto, N., Di Minin, A., Gregori, G.L., Lepore, D., Marinelli, L. & Spigarelli, F. (2020). The digital transformation of SMEs – a new knowledge broker called the digital innovation hub. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(6), 1263-1288.

Ho, C. T. (2009). The relationship between knowledge management enablers and performance. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 109(1), 98-117.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Oxford University Press.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The Tacit Dimension. University of Chicago Press.

Ramos Cordeiro, E., Lermen, F. H., Mello, C. M., Ferraris, A., & Valaskova, K. (2023). Knowledge management in small and medium enterprises: a systematic literature review, bibliometric analysis, and research agenda. Journal of Knowledge Management, 28(2), 590-612.

Senge, P. M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization. Doubleday.

von Krogh, G., Roos, J., & Slocum, K. (1994). An essay on corporate epistemology. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S2), 53-71.