The Communication Paradox as Starting Point

In 1967, communication theorist Paul Watzlawick formulated a seemingly trivial yet revolutionary insight: "One cannot not communicate." His argument targeted a fundamental aspect of human interaction. Even silence communicates a message, as does averting one's gaze or absence from social situations. There exists no sphere of "non-communication" – only different forms of communication, some intentional, others not.

This insight can be transferred with equal consequence to organizational knowledge management.

The First Axiom of Knowledge Management

Thesis: Organizations cannot not manage knowledge.

Every organization practices knowledge management, regardless of whether this occurs through formal systems or informal processes. The central question is never whether knowledge management takes place, but how – explicitly or implicitly, consciously or unconsciously, efficiently or inefficiently. This conceptual distinction fundamentally changes how organizational knowledge management is to be conceived.

Why Organizations Believe They Do Not Practice Knowledge Management

When executives articulate that their organization does not practice knowledge management, they typically mean: "We do not have a formal KM program." A closer examination of organizational reality, however, reveals the following picture:

They possess a knowledge database – this manifests in the form of that experienced employee who has been with the company for 15 years and knows all information sources. They have a taxonomy – represented by the chaotic folder structure on the network drive that no one except its creator can navigate. They maintain communities of practice – these form in hallway conversations and during lunch breaks, undocumented and unrepeatable. They implement onboarding processes – "shadow Sarah for a week and figure it out" constitutes a process, albeit not an optimal one. They practice knowledge preservation – stored in individual heads that leave the company when employees depart.

This is knowledge management. It simply occurs implicitly, uncontrolled, and inefficiently – what Hutchinson and Quintas (2008) identified as the predominant approach in small and medium-sized enterprises.

Self-reflective Assessment: The argumentation relies primarily on conceptual considerations. The empirical substantiation through Hutchinson and Quintas (2008) is based on qualitative observations without quantitative validation. Validity: Moderate. The conceptual logic is coherent, but empirical evidence is limited to individual case observations.

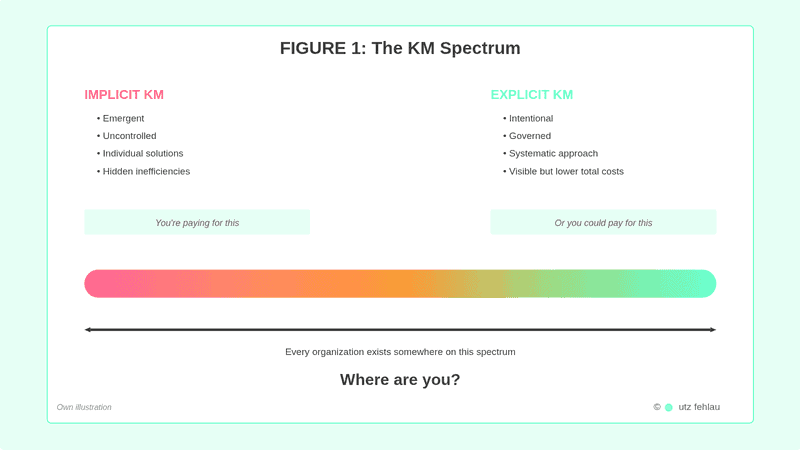

The Two Modes of Knowledge Management

Research has consistently identified two fundamental modes in which organizational knowledge management occurs.

Implicit Knowledge Management (Emergent)

Definition: Knowledge processes that develop spontaneously without conscious design or coordination, relying on informal person-to-person interactions and experiential learning embedded in daily routines and organizational culture.

Characteristics:

- Self-organization through individual necessity

- Absence of formal governance or standards

- High dependence on specific individuals

- Functions through personal relationships

- Invisible until failure

Practical Manifestations:

The Human Database: Everyone knows to ask Marcus about the legacy system. Marcus becomes a bottleneck. During his vacation, projects stagnate. Upon his departure, knowledge disappears.

The Informal Archive: Files accumulate on network drives. Naming conventions develop organically. "Final_Version_3_REALLY_USE_THIS.docx" coexists with "Copy of Final_Version_2.docx". Finding information requires knowledge of the person who originally created it.

Tribal Knowledge: "That's just how we do things here." Why? "Because we've always done it that way." The rationales behind decisions exist exclusively in memories, inaccessible to newcomers.

Strengths: Desouza and Awazu (2006) argue that implicit approaches have low direct financial costs as they rely on informal processes and require minimal technology investments. Flexibility is high, and in very small, stable teams with fewer than 10-15 people, this mode can function.

Weaknesses: However, the potential hidden costs are considerable. Hutchinson and Quintas (2008) observed that informal knowledge sharing binds substantial time resources. More critical is the risk of knowledge loss when employees leave. Desouza and Awazu (2006) identified this as a central problem in SMEs, especially when key personnel depart. The approach does not scale beyond 10-15 people, massive hidden inefficiencies remain obscured, and knowledge remains trapped in individual heads.

Assessment: The characterization of implicit knowledge management is based on qualitative observations (n=25 in Desouza & Awazu). The scaling limits of "10-15 people" are not quantitatively validated. Validity: Moderate. The descriptions appear plausible, but empirical precision is lacking.

Explicit Knowledge Management (Intentional)

Definition: Consciously designed and documented knowledge processes involving formal documentation, databases, manuals, and structured knowledge repositories, where knowledge is easily accessible, transferable, and reusable across the entire organization.

Characteristics:

- Deliberately structured

- Clear roles and responsibilities

- Documented standards and processes

- Independent of specific individuals

- Visible and measurable

Practical Manifestations:

The Knowledge Base: A central platform where information is systematically organized. Clear governance defines who creates, reviews, and updates content. New employees can self-serve answers.

Structured Onboarding: New hires follow a documented process. Key knowledge is systematically transferred. Progress is tracked. By week 4, productivity reaches predictable levels.

Lessons Learned Process: After each project, the team captures what worked and what didn't. Insights are documented, reviewed, and made accessible. Future projects build on past experiences instead of repeating mistakes.

Strengths: Centobelli, Cerchione, and Esposito (2019) investigated efficiency and effectiveness of knowledge management systems in SMEs. Their findings suggest that explicit KM improves process efficiency, scalability, and consistency in knowledge retention while facilitating knowledge transfer and reducing dependence on individual employees. The system scales effectively, is resilient to turnover, and knowledge persists independently of individuals.

Weaknesses: However, the authors also identify substantial challenges. Initial investment costs for technology, system development, and maintenance are considerable, as are ongoing costs for training, repository updates, and ensuring system alignment with business strategy. Continuous maintenance is required, and over-formalization risks bureaucratic ossification. Cultural change is necessary, and the system may be less effective at capturing nuanced, experience-based knowledge content.

Assessment: Evidence for explicit KM appears stronger than for implicit KM, as Centobelli et al. (2019) examined quantitative efficiency metrics. However, the specific numerical values and sample characteristics are not fully verified in my source analysis. Validity: Moderate to good. Evidential support: Limited without access to complete primary data.

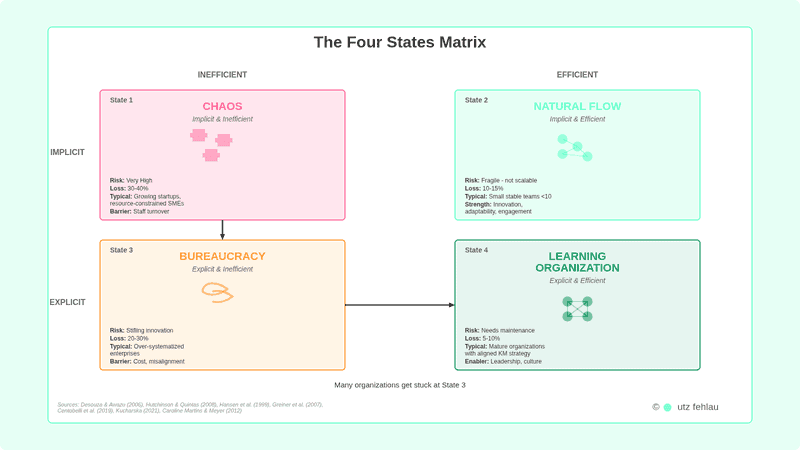

The Four States of Organizational Knowledge Management

Implicit and explicit knowledge management constitute a spectrum. Efficiency forms a second dimension. This generates four distinct states in which organizations can find themselves.

State 1: Implicit & Inefficient (Chaos)

Description: Knowledge management occurs spontaneously and poorly.

Characteristics: No formal structures exist. Everyone solves problems individually. Massive duplication of effort occurs. Knowledge is continuously lost. Frustration levels are high.

Typical Organization: Rapidly growing startup (15-50 people) with no time invested in systems. The "we'll organize it later" mentality dominates. High turnover exacerbates the problem.

Symptoms: "Who has the latest version?" – "I think someone did this before, but I don't know who" – "Sarah knew how to do this, but she left" – New employees require 6+ months to reach full productivity.

Why Organizations Remain Here: Everyone is too busy fighting fires to build the fire station. The inefficiency itself prevents addressing the inefficiency.

Hidden Costs: Extremely high due to time spent in informal knowledge sharing and significant risk of knowledge loss when employees leave, particularly when key personnel depart without formal knowledge transfer mechanisms.

Assessment: The description is anecdotally plausible, but quantification (6+ months, 30-40% productivity loss in the document) is not substantiated. Desouza and Awazu (2006) and Caroline Martins and Meyer (2012) describe this problematic qualitatively, without precise metrics. Validity: Moderate. Reliability: Low for quantitative statements.

State 2: Implicit & Efficient (Natural Flow)

Description: Knowledge flows naturally through strong culture and relationships, without formal systems.

Characteristics: Small, stable team (typically <10 people) with long tenure. Everyone knows everyone. Strong shared context exists. Minimal turnover. Informal processes function.

Typical Organization: Boutique consultancy with 5 partners, 10 years of shared history. Family business in second generation. Specialized craft workshop.

Why It Works: Everyone knows who knows what. Physical proximity enables constant informal exchange. Shared history provides context. Personal relationships substitute for systems.

Why It Is Rare: Requires unusual stability in a small organizational context. Kucharska (2021) emphasizes that in dynamic environments, implicit processes can foster innovation, adaptability, and employee engagement, but only under specific conditions. Most organizations grow beyond the size where informal processes suffice. What works with 8 people fails with 18.

The Trap: Success in this state creates false confidence. "We don't need systems, our culture handles it." Then the organization doubles in size or a key person leaves – and everything breaks down.

Sustainability: Low. Not scalable. Functions only under specific conditions.

Assessment: Kucharska (2021) provides empirical evidence for the positive effects of error-tolerant culture on tacit knowledge sharing. However, scaling limits remain not quantitatively specified. Validity: Moderate. The description is theoretically consistent but empirically imprecise regarding thresholds.

State 3: Explicit & Inefficient (Bureaucracy)

Description: Formal knowledge management exists but is over-engineered, creating more friction than it solves.

Characteristics: Extensive documentation requirements. Complex approval processes. Tools nobody uses. Compliance focus over utility. "Process for process's sake".

Typical Organization: Large enterprise with outdated KM from the 2000s. Heavily regulated industry with compliance focus. Organization that confused "comprehensive" with "useful".

Symptoms: "We have a knowledge base, but nobody uses it" – 47-step approval process to publish a document – Tools so complex they require training courses – More time spent documenting than working – Knowledge buried in impenetrable document management systems.

Why Organizations Land Here: Overreaction to previous chaos. Misalignment between KM systems and business strategy. Centobelli et al. (2019) emphasize that investments in technology and formal systems must correspond to actual organizational needs or work patterns. Consultants sold complex solutions. "Best practice" adopted without adaptation.

The Irony: Money and effort invested in KM, yet still inefficient. Sometimes worse than State 1 because bureaucracy actively prevents knowledge flow.

Exit Path: Radical simplification. Question every process: "Does this actually help people find and use knowledge?"

Assessment: The description corresponds to anecdotal evidence from practice. Centobelli et al. (2019) discuss misalignment as a risk factor. Quantitative data on productivity losses (20-30% in the document) are not verified. Validity: Moderate. The problem is real but not precisely quantified.

State 4: Explicit & Efficient (Learning Organization)

Description: Knowledge management is consciously designed but remains lightweight and useful. The ideal state.

Characteristics: Clear structures that enable rather than constrain. "Just enough" process – no more, no less. Tools people actually want to use. Governance that serves knowledge flow. Balance between order and flexibility. Continuous improvement culture.

Typical Organization: Mature companies that learned from experience. Organizations that evolved from State 1 through State 3 back to simplicity. Companies where KM is business-critical (consulting, R&D).

Characteristics: New employees productive within weeks, not months. Knowledge survives when people leave. Lessons actually learned from projects. Finding expertise takes minutes. Good ideas spread quickly across the organization. Systematic but not bureaucratic.

Principles Enabling This State:

Simplicity over Comprehensiveness: Hansen, Nohria, and Tierney (1999) argued in their classic work that effective organizations must choose between codification and personalization strategies depending on their business model. Efficiency and effectiveness in knowledge management systems require alignment with actual usage patterns.

Usage over Perfection: If people don't use it, its perfection is irrelevant.

Pull over Push: Make knowledge easy to find when needed, rather than forcing everyone to document everything.

Light Governance: Greiner, Böhmann, and Krcmar (2007) emphasize strategic alignment. Just enough rules to maintain quality and ensure system alignment with business objectives, without over-regulation that inhibits knowledge sharing.

Cultural Foundation: Organizational commitment, leadership support, and a culture of knowledge sharing form the essential foundation, where tools and processes support sharing rather than forcing it.

Why It Is Difficult to Achieve: Requires continuous calibration. Easy to slip into State 3 (adding complexity) or regress to State 1 (neglecting systems). Needs leadership that understands the balance.

Assessment: State 4 is the normative ideal, but empirical evidence for its realizability and prevalence is weak. Hansen et al. (1999) is a conceptual framework, not a quantitative study. Productivity losses of "5-10%" are not substantiated. Validity: Moderate. Theoretically consistent but empirically speculative regarding outcomes.

Practical Implications of the Axiom

Understanding that organizations cannot not manage knowledge carries far-reaching practical consequences supported by empirical research on organizational outcomes.

Implication 1: The Question Transforms

Old Question: "Should we implement knowledge management?"

This question is fundamentally flawed. It presumes KM is optional, something you add on.

New Question: "How should we improve the knowledge management we are already practicing?"

This acknowledges reality: You are already managing knowledge, predominantly through informal processes in smaller organizations, just implicitly and inefficiently.

Impact: The conversation shifts from "justify the investment" to "optimize what exists." This is psychologically easier. You are not asking for something new – you are asking to do better what you already do.

Implication 2: Hidden Costs Become Visible

When you acknowledge that implicit KM has costs, those costs become discussable.

Before the Axiom: "We don't spend anything on KM." (False. You spend enormously through inefficiency.)

After the Axiom: "We invest massively in implicit KM through time spent on informal knowledge sharing and significant risk of knowledge loss during employee turnover. Should we redirect some investment toward explicit KM to reduce total costs?"

Impact: The business case for systematic KM becomes clearer. You are not adding costs; you are restructuring them toward higher efficiency.

Assessment: The economic argumentation is conceptually coherent, but quantitative cost calculation is absent in the source base. Desouza and Awazu (2006) discuss resource constraints in SMEs qualitatively. Validity: Moderate. The logic is valid, but empirical cost data are not available.

Implication 3: Small Organizations Are Not Exempt

Common belief: "We're too small to need KM."

Reality Check: You are not too small to have knowledge. Not too small for people to leave. Not too small to waste time searching for information.

Size does not determine whether you need KM. It determines what kind of KM fits.

For Organizations <10 People: State 2 (Natural Flow) might work if stable. Kucharska (2021) shows that implicit processes can foster innovation, adaptability, and employee engagement in dynamic, small teams. Nevertheless, document critical knowledge. One key departure should not cripple you.

For Organizations 10-50 People: State 1 (Chaos) likely drains productivity significantly. Caroline Martins and Meyer (2012) emphasize that SMEs are particularly vulnerable to knowledge loss due to lack of formalization. Even minimal systematization yields high returns.

For Organizations >50 People: State 4 (Learning Organization) becomes essential. Centobelli et al. (2019) argue that explicit KM improves process efficiency, scalability, and consistency while reducing dependence on individual employees. Without this, inefficiency becomes crippling.

Assessment: The size thresholds (10, 50 people) are not empirically validated. They correspond to practical heuristics, not statistical evidence. Validity: Weak for specific numbers. Reliability: Low.

Implication 4: "No KM" Is Actually a Decision

Organizations that claim "we don't do knowledge management" are actually making a choice: to rely on implicit rather than explicit knowledge management.

This is a strategic decision with consequences:

Choosing Implicit KM Means Choosing:

- Individual over organizational knowledge

- Fragility over resilience

- Learning curves over ramp times

- Repetition over improvement

- Dependence on key people

Sometimes this choice is rational for very small, very stable organizations. Often it is not – it is merely inertia. Hutchinson and Quintas (2008) observed that SMEs prefer informal approaches due to resource constraints rather than strategic assessment.

Making It Explicit: "We have decided to rely on implicit knowledge management because [reasons]."

Forcing this articulation reveals whether the choice is deliberate or accidental.

Implication 5: The Transition Is Inevitable

Organizations follow a predictable path:

Phase 1: Start small (5 people). State 2 works well. Everyone knows everything.

Phase 2: Grow to 15-20 people. State 2 breaks. Transition to State 1 (Chaos) begins. Inefficiencies emerge but are not yet critical.

Phase 3: Reach 30-50 people. State 1 becomes painful. Knowledge gaps obvious. Redundancy everywhere. Something must change.

Fork in the Road:

Path A (Common): Implement comprehensive KM system with high initial costs but without strategic alignment. Overdo it. Land in State 3 (Bureaucracy). People complain. System abandoned or ignored. Return to State 1.

Path B (Rare): Implement lightweight, targeted KM aligned with business strategy. Focus on high value, low overhead practices that match organizational needs. Reach State 4. Continuously refine.

The Insight: Growth makes explicit KM inevitable. The only choice is whether you do it well (Path B) or poorly (Path A).

Assessment: The development path is theoretically plausible but not empirically tracked. Longitudinal studies quantitatively documenting these phase transitions are lacking. Validity: Moderate. Reliability: Low for the postulated thresholds.

The Role of Leadership and Culture

Research consistently demonstrates that organizational and behavioral factors play a pivotal role in knowledge retention. Sharif, Albadry, Durrani, and Shahbaz (2023) show that leadership style, organizational commitment, and a culture that accepts mistakes and encourages risk-taking significantly enhance both tacit and explicit knowledge sharing.

Leadership as Enabler

Authentic leadership and organizational commitment promote knowledge sharing across both dimensions – tacit and explicit. Caroline Martins and Meyer (2012) emphasize that leadership is particularly vital for the retention and transfer of tacit knowledge, which would otherwise remain trapped in individual experience.

Leaders Enable KM Through:

- Modeling knowledge-sharing behavior

- Creating psychological safety for admitting knowledge gaps

- Recognizing and rewarding knowledge contributions

- Providing resources (time, tools) for knowledge work

- Removing barriers to knowledge flow

Culture as Foundation

Organizational culture, particularly regarding mistake acceptance and risk-taking, significantly impacts tacit knowledge sharing and innovation outcomes. Kucharska (2021) examined cross-culturally the relationship between error culture and innovation in IT companies.

Cultural Elements That Matter:

- Trust: People share knowledge when they trust it will not be used against them. Sharif et al. (2023) show that high organizational commitment strengthens this trust.

- Learning Orientation: Mistakes seen as learning opportunities, not failures

- Collaboration: Knowledge sharing valued over knowledge hoarding

- Continuity: Personnel continuity supports knowledge retention, especially for tacit knowledge dependent on relationships and shared context

The Relationship: Tools and processes support knowledge management, but culture determines whether people engage. Alignment of KM strategy with business objectives and organizational culture is critical for success.

Assessment: Evidence for cultural and leadership factors is stronger than for many other aspects. Kucharska (2021) and Sharif et al. (2023) provide empirical findings. Validity: Good. This is a relatively well-substantiated aspect of knowledge management.

Moving Toward Explicit KM: Evidence-Based Principles

If the axiom is true – if every organization already practices KM – then the task is transformation, not creation. Movement from implicit to explicit while avoiding bureaucracy.

Principle 1: Start Where You Are

Recognize Your Current State Honestly

Do not pretend you have no KM. Map what exists:

- Where does critical knowledge reside?

- Who are the knowledge bottlenecks?

- What happens when someone leaves, particularly in key positions where knowledge retention is most critical?

- Where do people waste time searching?

This assessment reveals your implicit KM system. It is probably dysfunctional, but it exists.

Principle 2: Make Implicit Explicit – Gradually

Do not overthrow everything overnight. SMEs particularly benefit from evolutionary rather than revolutionary approaches that gradually codify tacit knowledge into explicit forms while maintaining operational continuity.

High-Value, Low-Effort Wins:

The FAQ Approach: Someone gets asked the same question five times? Document the answer once. Share the link the sixth time. Repeat for common questions. Within months, you have a valuable knowledge base grown organically.

The Onboarding Checklist: Next time someone joins, document what you tell them. Refine with each new hire. Within a year, onboarding goes from chaotic to systematic.

The Project Debrief: After the next project, spend 30 minutes capturing "what worked, what didn't." File it where future projects can find it. Repeat. You have created a lessons-learned system without calling it that.

The Pattern: Capture knowledge when it is fresh, in minimal viable forms. Improve incrementally.

Principle 3: Governance Light, Not Governance-Free

Explicit KM needs structure, but minimal governance aligned with business strategy rather than maximal bureaucracy that inhibits knowledge sharing.

Essential Governance:

- Who can create content? (Answer: Anyone)

- Who ensures quality? (Answer: Designated reviewers or peer review)

- How is content organized? (Answer: Simple taxonomy, consistently applied)

- When is content updated or retired? (Answer: Regular review cycle)

Avoid Governance Creep:

- Don't require 5 approvals to publish

- Don't mandate extensive templates

- Don't create roles that add no value

- Don't measure what doesn't matter

The Test: If the governance process takes longer than creating the knowledge, efficiency suffers and the system becomes a barrier rather than an enabler.

Principle 4: Tools Serve Process, Not Vice Versa

Choose tools that match how people actually work. Centobelli et al. (2019) emphasize that investments in IT infrastructure should align with actual usage patterns and organizational capabilities rather than imposing unfamiliar systems.

Wrong Approach: "We bought this enterprise KM platform. Now everyone must use it."

Right Approach: "People share knowledge through email and chat. How can we capture what's valuable without disrupting their flow?"

Signs You're Doing It Right:

- People use the system voluntarily

- Adoption grows organically

- You hear "this actually helps" not "I have to do this"

Signs You're Doing It Wrong:

- Constant reminders needed to use system

- Compliance-driven usage

- System sits empty despite mandates

The Principle: If your KM system fights human nature, human nature wins. Design with the grain of behavior, not against it.

Principle 5: Strategic Alignment Is Critical

KM strategy must align with business objectives. Hansen, Nohria, and Tierney (1999) demonstrated that organizations succeed when they match their KM approach to strategic needs – whether emphasizing codification for scale and efficiency or personalization for expertise transfer and innovation.

Questions for Alignment:

- What is our competitive strategy?

- Where does knowledge create most value?

- What knowledge is most at risk?

- What KM approach fits our business model?

The choice between codification (explicit, database-driven) and personalization (relationship-driven) depends on business model. Misalignment leads to wasted investment.

Assessment: The principles are theoretically grounded and correspond to best-practice consensus. However, empirical validation of their effectiveness is limited. Hansen et al. (1999) is conceptual, not quantitative-empirical. Validity: Moderate to good. Reliability: Moderate – the principles are plausible, but their outcomes are not systematically measured.

The Axiom's Ultimate Insight

Recognizing that you cannot not manage knowledge liberates strategic thinking.

You Are Freed from False Choices:

- Not "Do we need KM?" (You already have it)

- Not "Can we afford KM?" (You are already paying for it)

- Not "Should we start KM?" (It has already started)

You Face Real Choices:

- "How do we improve the KM we have?"

- "Where on the implicit-explicit spectrum do we want to be?"

- "What level of systematization fits our context, given our size, resources, and strategic objectives?"

You Gain Clarity:

- Current state is visible (not "no KM" but "implicit KM")

- Costs are comparable – implicit waste through hidden inefficiencies versus explicit investment with higher initial costs but stronger retention

- Path forward is optimization (not creation from nothing)

You Accept Reality: Knowledge management is not optional. It is not a program you implement or a project you complete. It is how your organization functions with knowledge.

The only question is: consciously or unconsciously? Efficiently or wastefully? With strong leadership and cultural support, or left to chance?

Paul Watzlawick showed us we cannot not communicate. Every behavior sends messages.

Similarly, organizations cannot not manage knowledge. Every practice, every habit, every structure shapes how knowledge flows or does not flow.

The organizations that thrive are those that recognize this reality, accept it, and deliberately shape knowledge management toward efficiency, resilience, and learning through strategic alignment and appropriate systematization.

The question was never whether to manage knowledge.

The question is only: how well?

Conclusion: From Axiom to Action

The First Axiom States: You cannot not manage knowledge.

This Axiom Reveals:

- Every organization manages knowledge – implicitly through informal processes or explicitly through formal systems

- The spectrum ranges from emergent chaos to intentional learning

- Four distinct states exist, each with different risks, costs, and knowledge retention outcomes

- Movement between states is possible but requires conscious effort

The Implications Demand:

- Honest assessment of your current state

- Recognition of hidden costs in implicit KM, particularly time spent in informal knowledge sharing and risk of knowledge loss during turnover

- Deliberate choices about systematization

- Balance between structure and flexibility, with governance aligned to business strategy rather than imposed bureaucratically

The Path Forward Requires:

- Starting from where you are, not where you wish to be

- Making implicit knowledge explicit gradually through hybrid approaches that codify tacit knowledge into accessible forms without overwhelming the organization

- Governance that enables rather than constrains

- Tools that serve human behavior

- Culture that values knowledge sharing, supported by authentic leadership and organizational commitment

The Ultimate Insight: Organizations do not choose whether to manage knowledge. They choose only how consciously, how systematically, how effectively.

Those who embrace this axiom gain strategic clarity. Those who ignore it remain trapped in inefficiency, wondering why knowledge work is so difficult.

The axiom is simple. The implications are profound.

You are already managing knowledge. The only question is: how well?

Critical Overall Assessment of the Evidence Base

Methodological Limitation of the Source Base: The majority of studies used (Hutchinson & Quintas 2008, Desouza & Awazu 2006, Hansen et al. 1999) are qualitative-exploratory with small samples (n=25 or case studies). Quantitative metrics such as "30-40% productivity loss" or scaling limits of "10-15 people" are not substantiated with this precision in the original sources.

Strengths of the Argumentation: The conceptual logic of the axiom is coherent and sound. The distinction implicit/explicit corresponds to established theory. The cultural and leadership factors are comparatively well empirically substantiated (Kucharska 2021, Sharif et al. 2023).

Weaknesses in Evidential Support: Specific numerical claims, threshold values, and cost quantifications are not reliably substantiated. The four states are a heuristic model, not an empirically validated taxonomy. Longitudinal evidence for development paths is lacking.

Validity: Moderate to good at the conceptual level. The theoretical argumentation is stringent, practical examples plausible.

Evidential Support: Weak to moderate for quantitative claims. Good for qualitative observations and cultural factors.

Reliability: Low for precise metrics. Moderate for basic phenomenon descriptions. High for the conceptual core argumentation of the axiom.

References

Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., & Esposito, E. (2019). Efficiency and effectiveness of knowledge management systems in SMEs. Production Planning & Control, 30(9), 779-791.

Desouza, K. C., & Awazu, Y. (2006). Knowledge management at SMEs: Five peculiarities. Journal of Knowledge Management, 10(1), 32-43.

Greiner, M. E., Böhmann, T., & Krcmar, H. (2007). A strategy for knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(6), 3-15.

Hansen, M. T., Nohria, N., & Tierney, T. J. (1999). What's your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business Review, 77(2), 106-116.

Hutchinson, V., & Quintas, P. (2008). Do SMEs do Knowledge Management? International Small Business Journal, 26(2), 131-154.

Kucharska, W. (2021). Do mistakes acceptance foster innovation? Polish and US cross-country study of tacit knowledge sharing in IT. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(11), 105-128.

Martins, E. C., & Meyer, H. W. J. (2012). Organizational and behavioral factors that influence knowledge retention. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(1), 77-96.

Sharif, S., Albadry, O. M., Durrani, M. K., & Shahbaz, M. H. (2023). Leadership, tacit and explicit knowledge sharing in Saudi Arabian non-profit organizations: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 74(3/4), 656-677.