In today’s knowledge-driven economy, knowledge itself has become one of the most critical strategic assets for organizations (Tangible Vs. Intangible Assets | ). Companies increasingly recognize that effectively transferring knowledge—whether it’s expert know-how, best practices, or innovative ideas—is crucial for maintaining competitiveness, fostering innovation, and supporting continuous organizational learning (Knowledge Transfer: A Key to Improving Employee Performance). This article provides an overview of key strategies that modern organizations use to facilitate knowledge transfer, ranging from people-focused approaches (like communities of practice, mentoring programs, and job rotations) to technology-enabled solutions (such as intranet knowledge bases, collaboration platforms, and knowledge maps) and process-oriented methods (like lessons-learned reviews and best-practice documentation). It also highlights major challenges that often hinder smooth knowledge flow, including individual resistance to sharing, siloed organizational structures, and difficulties in capturing tacit (unwritten) knowledge. Effective knowledge management (KM) frameworks—and tools like knowledge maps that visually pinpoint where critical expertise resides (What is Knowledge Mapping and How to Use It? | MindManager)—play a pivotal role in overcoming these barriers. The objective of the article is to deliver a comprehensive analysis of knowledge transfer strategies and challenges in modern organizations, offering practical insights into how firms can better leverage their collective knowledge for improved performance and innovation.

1. Introduction

1.1 The evolving landscape of organizational knowledge

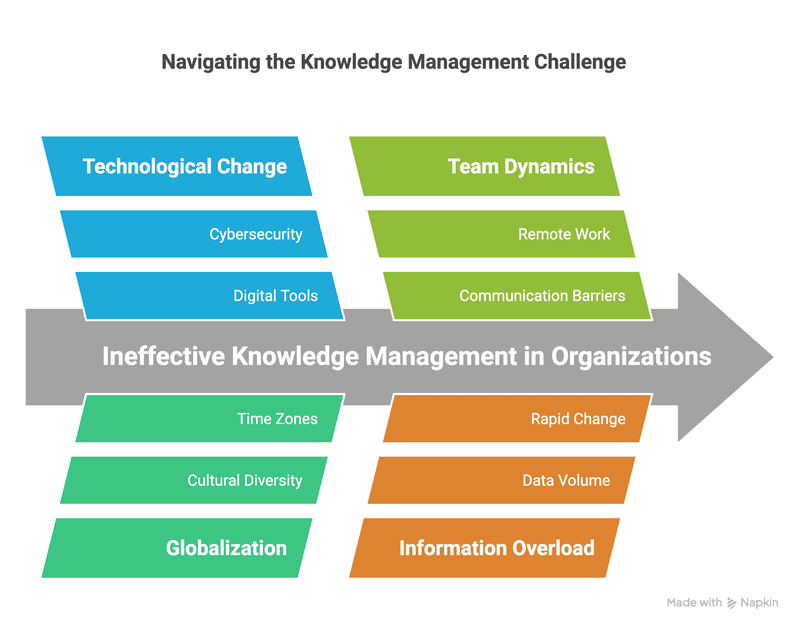

Today’s business environment is more complex and fast-paced than ever. Rapid technological change, globalization, and the shift toward a knowledge economy mean that companies must systematically manage what they know to survive and thrive. As management guru Peter Drucker observed, “knowledge has become the key economic resource and the dominant—and perhaps even the only—source of competitive advantage. In modern organizations, intangible assets like know-how, expertise, and intellectual capital now comprise the bulk of value—by 2015, about 84% of the market value of S&P 500 companies came from intangibles (up from just 17% in 1975) (Tangible Vs. Intangible Assets | ) (Tangible Vs. Intangible Assets | ). This profound shift underscores why systematic knowledge management is essential: enterprises need ways to capture, organize, and leverage knowledge amid constant change. The digital transformation has further altered how knowledge flows; remote and distributed teams cannot rely on hallway conversations for information exchange. Instead, firms require robust knowledge-sharing practices and tools to ensure that critical insights reach the right people at the right time. In an era of information overload and rapid turnover, treating organizational knowledge as a managed asset is no longer optional—it’s a strategic necessity for coping with complexity.

1.2 The significance of knowledge transfer

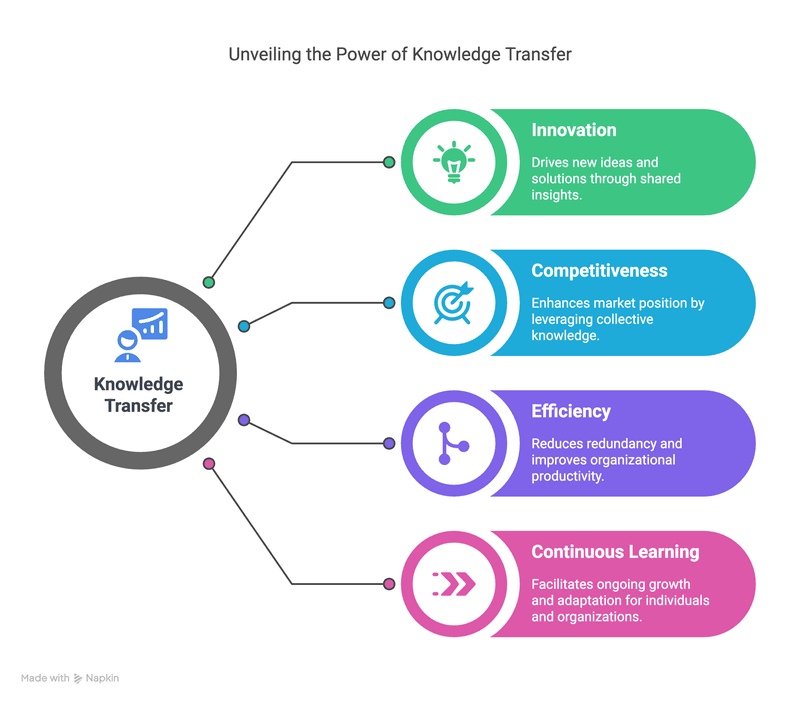

Knowledge transfer refers to the process by which knowledge (information, skills, or expertise) is passed from one person or group to another. In formal terms, it is often defined as the extent to which one unit “learns from or is affected by the experience of another” within the organization (Knowledge Transfer Within Organizations: Mechanisms, Motivation, and Consideration | Annual Reviews). Effective knowledge transfer is a linchpin of organizational success: it enables the best ideas and practices to permeate the company, rather than remaining siloed. This sharing of knowledge is directly linked to competitiveness – as Drucker noted, knowledge is now perhaps the primary source of competitive advantage. When employees freely exchange know-how, the organization can respond faster to market changes and outperform rivals. Innovation also thrives on knowledge transfer, because new ideas often emerge by building on existing insights; employees can combine diverse expertise to create novel solutions (Knowledge Transfer: A Key to Improving Employee Performance). In terms of efficiency, a strong knowledge-sharing culture prevents “reinventing the wheel.” Lew Platt, former CEO of HP, famously quipped, “If only HP knew what HP knows, we would be three times more productive” (Tacit Knowledge Vs. Explicit Knowledge), highlighting how untapped internal knowledge hinders performance. Furthermore, knowledge transfer fuels continuous learning – both for individuals (as they learn from peers) and for the organization as a whole. It underpins the concept of the learning organization, wherein companies continually improve by retaining and applying lessons learned. In short, efficient knowledge transfer boosts innovation, improves decision-making, increases productivity, and helps firms adapt and learn, making it a critical driver of long-term success.

1.3 Article objectives and structure

The objective of this article is to identify effective strategies for knowledge transfer and to examine the challenges that organizations face in this domain. The analysis is organized as follows. Section 2 defines fundamental concepts – distinguishing data, information, and knowledge (including explicit vs. tacit knowledge) – and explains knowledge transfer in relation to learning. Section 3 describes key knowledge transfer strategies, grouped into people-focused approaches, technology-enabled solutions, and process-oriented methods. Section 4 discusses common challenges to effective knowledge transfer at both the individual and organizational level (from reluctance to share up to structural silos). Section 5 considers knowledge transfer in specific contexts by contrasting the dynamics in small and mid-sized enterprises (SMEs) versus large organizations. We then outline how to measure knowledge transfer success in Section 6, covering practical metrics and indicators. Section 7 concludes with a summary of findings and future directions, including the influence of digital transformation and AI on knowledge sharing. A brief Factsheet at the end summarizes the main strategies and challenges for quick reference. Through this structured approach, the article aims to provide readers with an authoritative yet practical guide to improving knowledge transfer within their organizations.

2. Defining Knowledge and Knowledge Transfer

2.1 Conceptualizing knowledge

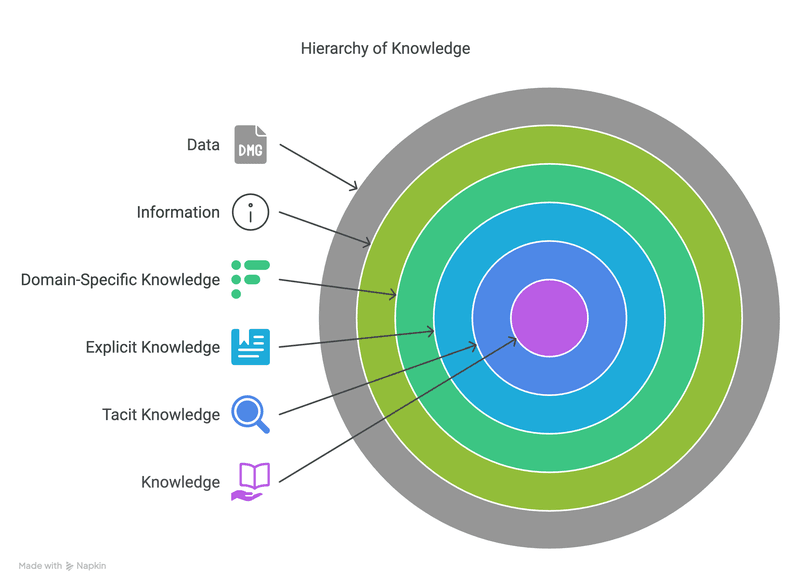

It’s important to distinguish data, information, and knowledge. Data consists of raw facts or figures without context. Information is data that has been processed and given context, making it meaningful (Data vs Information vs Knowledge: What Are The Differences? – Tettra) – for example, a report or graph that interprets raw data. Knowledge goes further: it is information combined with experience, insight, and the ability to apply it (Data vs Information vs Knowledge: What Are The Differences? – Tettra). In essence, knowledge is the understanding or “know-how” that enables effective action or decision-making.

Knowledge comes in different forms, notably explicit vs. tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is formal and codified – the kind you can easily document and share (like manuals, checklists, or databases). Tacit knowledge, by contrast, lives in people’s heads – it’s personal know-how, intuition, and skills that are hard to articulate. Michael Polanyi famously noted “we can know more than we can tell,” capturing how tacit know-how often defies easy articulation. Tacit knowledge is essentially knowledge “in someone’s head,” and the challenge is to make that implicit know-how explicit so it can be shared (Tacit Knowledge Vs. Explicit Knowledge). Because tacit knowledge is unwritten and experience-based, transferring it usually requires direct person-to-person interaction (e.g. mentoring, observation) rather than just handing over documents.

Knowledge is also domain-specific. Expertise in one domain (say, software engineering) may not be fully meaningful in another domain (say, marketing) without context. Each field has its own jargon, frameworks, and background assumptions. This means knowledge that is highly relevant in one area might not be directly applicable in another without translation or adaptation. Understanding the domain context is crucial when transferring knowledge: the more shared context the giver and receiver have, the easier it is to communicate the knowledge. In practice, organizations map their knowledge domains (for instance, finance, marketing, R&D, etc.) and identify subject-matter experts in each. Knowing what kind of knowledge is being dealt with (data vs. information vs. knowledge, explicit vs. tacit, and domain-specific nuances) is fundamental before one can effectively manage or transfer that knowledge.

2.2 Understanding knowledge transfer

In an organizational context, knowledge transfer encompasses all activities that enable knowledge to move from one person or group to another. The terms knowledge sharing or knowledge exchange are often used interchangeably to describe this collaborative process of passing along useful know-how. For example, one definition describes knowledge sharing as “transferring information, insights, skills, or expertise from one individual or group to others… a collaborative process where employees voluntarily share their expertise and best practices with their peers to enhance collective learning and problem-solving” (The Importance of a Knowledge Sharing Culture (2025)). In essence, knowledge transfer is more than just communication – it implies that the recipient actually absorbs the knowledge and can use it, thus becoming wiser or more capable. If knowledge is simply sent but not understood or applied by others, true transfer hasn’t occurred.

Knowledge transfer is closely linked to learning processes in organizations. When done effectively, it means that one unit or individual learns from the experience of another. Rather than each team learning solely through trial and error, knowledge transfer allows a company’s successes and lessons learned to benefit others across the organization (Knowledge Transfer Within Organizations: Mechanisms, Motivation, and Consideration | Annual Reviews). In this way, it is a primary mechanism of organizational learning – the organization as a whole “remembers” and builds on what is known, rather than forgetting or duplicating work. For instance, an engineer sharing a solution to a design problem with colleagues enables the whole engineering team to solve similar issues faster in the future. Research shows that organizations that excel at internal knowledge transfer are more productive and even have higher survival rates (Knowledge Transfer Within Organizations: Mechanisms, Motivation …), because they continuously leverage collective wisdom. In summary, knowledge transfer is about ensuring that knowledge travels to where it is needed and is effectively internalized there, driving continuous learning and improvement.

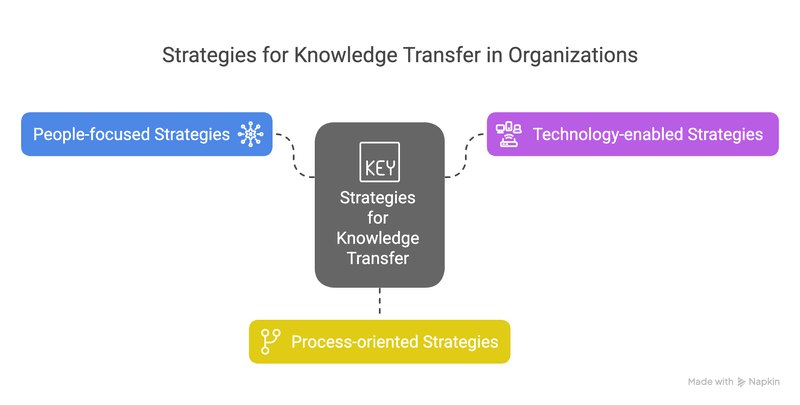

3. Strategies for Knowledge Transfer in Organizations

3.1 People-focused strategies

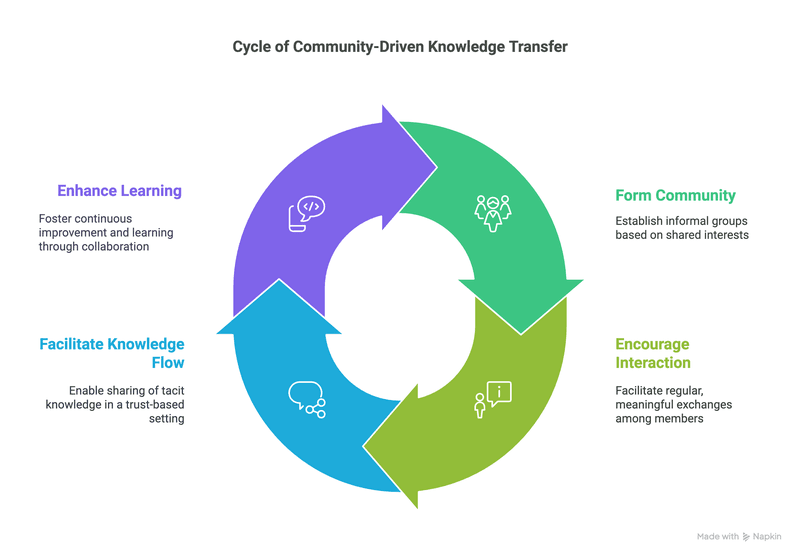

Many knowledge transfer solutions center on people and interactions. A foundational approach is to cultivate Communities of Practice (CoPs) – informal networks of people who share a common interest or profession and learn by interacting regularly. Etienne Wenger, who coined the term, defines CoPs as “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (Communities of Practice: Fuel Your Knowledge Management). In an organization, a CoP might be a cross-departmental forum where engineers exchange design tips or sales reps share customer insights. Companies can encourage CoPs by giving employees time and space to meet (virtually or in person) and by seeding internal forums for discussion. These communities facilitate tacit knowledge flow – employees pick up insights from peers in a trust-based setting that formal training might not capture.

Another people-centric strategy is mentoring and coaching. Pairing less experienced employees with seasoned mentors helps transfer tacit knowledge through apprenticeship. Mentors share not just facts but also tricks of the trade and hard-earned lessons from experience. A good mentorship program accelerates onboarding and leadership development by ensuring critical know-how is passed down. (Sometimes “reverse mentoring” is also used – for example, junior staff teaching senior colleagues about new technologies.) The key is a two-way relationship of trust. Effective mentoring doesn’t just answer questions – it immerses the junior person in the mentor’s way of thinking and problem-solving. This preserves institutional knowledge and builds capability in the next generation (The Importance of a Knowledge Sharing Culture (2025)).

Job rotation and cross-training programs are another powerful tool. By rotating employees through different roles or departments, companies enable staff to broaden their skills and share insights between areas. Someone moving from marketing to product development, for instance, brings marketing know-how into their new team and carries technical insights back to marketing later. This cross-pollination spreads best practices and breaks down silos. Rotation programs essentially create “knowledge bridges” between departments, as employees carry their experience with them. Studies show that employee rotation programs can significantly boost knowledge sharing by giving staff firsthand exposure to other functions (How can organizations ensure successful knowledge transfer …). The result is a more versatile workforce with a shared understanding across units.

Finally, consider the role of informal communication. A great deal of workplace knowledge sharing happens through casual interactions – the hallway chats, coffee break conversations, or spontaneous “Hey, can I pick your brain?” moments. Smart organizations foster these exchanges by creating opportunities for people to connect informally (for example, hosting “lunch and learn” sessions or maintaining internal social networks). The goal is to build a culture where asking questions and sharing tips is encouraged, not seen as an interruption. Such open communication tends to uncover tacit knowledge and spread it organically, helping knowledge reach where it’s needed. In a truly collaborative culture that breaks down silos (The Importance of a Knowledge Sharing Culture (2025)), employees are far more likely to volunteer information and help each other, ensuring knowledge flows freely across the organization. By leveraging people-focused strategies like these, companies tap into their richest knowledge base: the collective expertise of their employees.

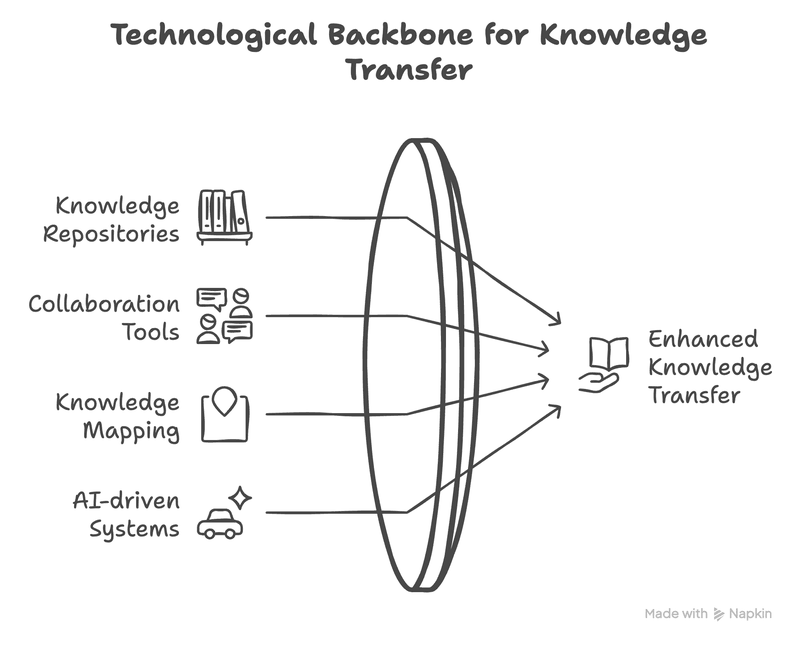

3.2 Technology-enabled strategies

Modern organizations rely on various technologies to support knowledge transfer. One fundamental set of tools are knowledge repositories – centralized digital libraries where explicit knowledge is stored and made accessible. This includes intranet portals, internal knowledge bases, or wikis containing things like procedure manuals, how-to guides, research reports, FAQs, and lessons learned. These repositories serve as a single source of truth; employees can search and retrieve documented solutions instead of reinventing the wheel. The content is typically indexed or tagged for easy lookup. By capturing experts’ insights in a repository, an organization ensures that knowledge endures beyond any one individual and is available on-demand to anyone who needs it.

In parallel, collaboration and communication tools play a vital role in everyday knowledge exchange. Enterprise social networks and messaging platforms (e.g. Slack, Microsoft Teams, Yammer) enable real-time sharing across teams and locations. Through group chats or discussion forums, employees can ask questions and get answers from colleagues quickly, share tips, and collectively troubleshoot issues. In effect, these tools turn daily communication into a vehicle for knowledge transfer. For example, an engineer might post a query on an internal Slack channel and receive helpful responses from peers in other offices, spreading knowledge instantly across geographic or departmental boundaries. The conversations themselves become searchable archives that others can later consult. By leveraging such collaboration platforms, companies make tacit knowledge and advice visible and accessible across the organization in a way that email or face-to-face chats alone cannot.

Organizations are also adopting knowledge mapping techniques to visualize and navigate their intellectual capital. A knowledge map is a visual guide that shows where knowledge resides in the organization and who has expertise on a given topic (What is Knowledge Mapping and How to Use It? | MindManager). In practice, it might be an interactive diagram or directory that links subject areas to the key experts and information resources associated with them. For instance, a knowledge map could reveal which team or person to approach for insights on “customer feedback analytics,” and point to relevant reports or databases. This helps employees quickly find the right knowledge source without wasting time. Knowledge maps can also illuminate gaps or single points of failure (e.g. if one person holds critical knowledge). By mapping out knowledge domains and owners, companies improve knowledge discoverability and reduce the risk of important know-how being hidden or lost.

Finally, AI-driven knowledge systems are an emerging frontier to enhance knowledge transfer. Artificial intelligence is being used to improve how knowledge is discovered and shared (AI in Knowledge Management: Overview, Key Features, and Top Tools). For example, AI-powered search engines can understand natural language queries and context, providing employees with precise answers from the company’s knowledge base. Some organizations deploy internal chatbots or virtual assistants that employees can ask questions; the AI pulls from documented policies or past Q&A to respond instantly, simulating an experienced colleague’s guidance. AI can also automatically organize content (by tagging or summarizing documents) and even proactively recommend relevant knowledge to users based on their role or query. These capabilities significantly reduce the time people spend hunting for information. By embedding AI in their knowledge platforms, organizations aim to deliver the right information at the right time – which accelerates problem-solving and helps employees learn from a vast pool of collective knowledge without being overwhelmed by it. In summary, technology tools – from simple intranets to advanced AI assistants – form a backbone for knowledge transfer by enabling documentation, searchability, collaboration, and on-demand access to the organization’s collective know-how.

3.3 Process-oriented strategies

In addition to people and tools, organizations implement structured processes to facilitate knowledge transfer. One widely used practice is conducting “lessons learned” reviews (or after-action reviews) at the end of projects or major events. The idea is to systematically capture what was learned – both successes and mistakes – so that others can benefit from that experience in the future. A lesson learned is essentially a piece of knowledge gained through experience, documented and shared (How To Incorporate Lessons Learned And Retrospectives … – Forbes). For example, a project team might record that a certain approach reduced cost, or that a particular error occurred and how to avoid it next time. By holding post-project debriefs and storing the insights in a lessons-learned repository, companies build an institutional memory. Future teams can search this repository to avoid repeating past mistakes and to replicate past successes. This process-oriented approach turns every project into a learning opportunity and promotes continuous improvement.

Similarly, many firms encourage best practice sharing. When a team discovers an especially effective method or tool, that “best practice” is documented (often as a brief case or guideline) and then disseminated across the organization. Some organizations hold regular knowledge-sharing meetings or publish internal newsletters highlighting new best practices. By standardizing proven techniques, they ensure that high-quality methods are adopted widely instead of remaining isolated in one department.

Another process-level strategy is to perform periodic knowledge audits. A knowledge audit is a systematic assessment of what critical knowledge exists within the organization, where it resides, and where there are gaps or risks. For instance, an audit might reveal that only one veteran employee understands a key client relationship or a legacy system – a clear knowledge retention risk. With that insight, management can take actions such as having that expert train colleagues or codify their knowledge into documents. Knowledge audits often involve mapping knowledge assets and surveying staff about informational needs, ultimately leading to plans for addressing weak spots in knowledge coverage.

Finally, organizations emphasize standardization and documentation of processes. By developing clear standard operating procedures, manuals, and process maps, companies transfer knowledge from individual minds into tangible form. This not only makes day-to-day operations more consistent but also makes it easier to onboard new employees (since much of the know-how is documented). It aligns with quality management principles – for example, ISO 9001 standards include requirements to manage “organizational knowledge” needed for operations. In short, process-focused strategies embed knowledge transfer into the organization’s routines: capturing lessons, broadcasting best practices, auditing knowledge needs, and documenting crucial processes. These measures create an environment of continuous learning and knowledge continuity.

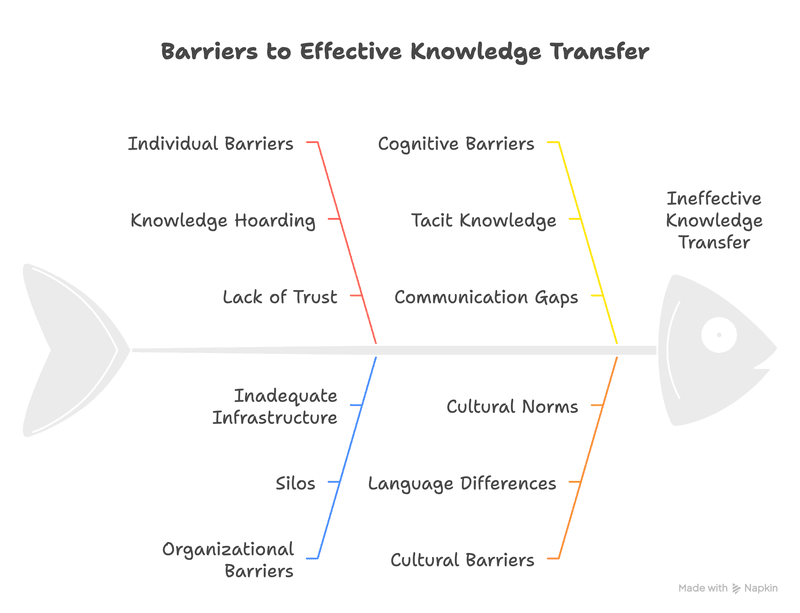

4. Challenges to Effective Knowledge Transfer

4.1 Individual-level barriers

Even when the right tools and processes are in place, knowledge transfer ultimately depends on people’s willingness and ability to share. A number of human factors can impede this. One common barrier is knowledge hoarding – when employees resist sharing what they know. They might feel that their specialized knowledge gives them job security or status, so they fear losing an edge if they give it away. In some cases, individuals withhold information to maintain control or a competitive advantage (The Importance of a Knowledge Sharing Culture (2025)). This behavior undermines collective learning, as valuable insights stay siloed with one person. Related to this is a lack of motivation or incentives to share knowledge. If sharing is not recognized or rewarded, busy employees may see no personal benefit in taking time to document their expertise or answer a co-worker’s questions. As a result, they focus on their own tasks and priorities. Without explicit incentives or a culture that values collaboration, knowledge transfer often takes a back seat (The Importance of a Knowledge Sharing Culture (2025)).

Another critical factor is trust. People are much more inclined to share know-how if they trust that it won’t be misused or held against them. If the workplace climate is political or blame-oriented, employees may hesitate to admit mistakes or volunteer lessons learned. They might worry: “Will sharing this information come back to haunt me?” A lack of trust in colleagues or leadership can thus dampen open knowledge exchange. In fact, research identifies low trust as a top barrier to knowledge sharing in organizations (Overcoming Trust as a Barrier to Knowledge Sharing | APQC). Building a safe environment – where people feel their contributions are valued and won’t backfire – is crucial to overcoming this hurdle.

Additionally, there are cognitive and communication barriers. Experts often find it challenging to articulate tacit knowledge that they perform intuitively. We all experience the “curse of knowledge” – once we know something well, we forget what it’s like not to know it. This can lead to experts explaining things using jargon or skipping steps, leaving less experienced colleagues confused. In other cases, people may not realize that certain knowledge they have is valuable to others (they assume it’s common knowledge when it isn’t). These factors hinder effective transfer, especially of complex know-how. Overcoming them requires training in communication skills and conscious effort by experts to step into the learner’s shoes. Techniques like storytelling or using analogies can help convey complex ideas in more relatable terms.

Language and cultural differences can also pose individual-level challenges, especially in global organizations. Team members with different native languages might struggle to express or understand nuances, and even within one language, professional jargon can differ (an engineer and a marketer might use the same word to mean different things). Studies show that language diversity is an important factor influencing knowledge sharing in international teams (The Impact of Language Diversity on Knowledge Sharing Within …). Likewise, culture plays a role – in some cultures employees might be less inclined to speak up or challenge ideas, which can limit knowledge exchange. Being aware of these differences and encouraging clear, inclusive communication is key to mitigating this barrier.

In summary, individual barriers – from personal attitudes (hoarding, lack of trust) to cognitive biases and communication gaps – can significantly slow the flow of knowledge. Addressing these requires both cultural interventions (to build trust and incentivize sharing) and support for individuals (training them to communicate their knowledge effectively and making it feel safe and worthwhile to do so).

4.2 Organizational-level barriers

At the organizational level, structural and cultural factors can either facilitate or hinder knowledge transfer. A major barrier is the presence of silos – when departments or business units operate in isolation with little communication across boundaries. In a siloed organization, knowledge tends to stay trapped within teams rather than flowing freely. A culture that doesn’t prioritize collaboration or transparency will reinforce these silos (The Importance of a Knowledge Sharing Culture (2025)). For example, if the sales department and engineering department rarely interact, each may develop expertise that the other never hears about. This fragmentation means the organization fails to leverage its full knowledge base. Overcoming silos requires deliberate efforts by leadership to encourage cross-functional projects, open communication channels, and a shared sense of purpose across units.

Another challenge is inadequate knowledge-sharing infrastructure. If the organization provides weak communication channels or poor technology support, employees may struggle to share. No efficient platform to exchange information (or an overly cumbersome one) becomes a significant barrier (The Importance of a Knowledge Sharing Culture (2025)). For instance, a company without a good internal knowledge portal or collaboration tool makes it onerous for employees to publish what they know or find what others have shared. Especially in large or dispersed organizations, ineffective knowledge systems can cause important know-how to “slip through the cracks.” Investing in user-friendly knowledge management systems and integrating them into daily workflows is critical to avoid this.

Resource and time constraints imposed by the organization can also impede knowledge transfer. If management does not allocate time for employees to document insights or mentor others, knowledge activities will be squeezed out by immediate work demands. In many cases, organizations view knowledge sharing as extra work rather than part of normal process. A telling example is in smaller firms where formal KM is often skipped because it’s seen as too costly or time-consuming (The Strategic Importance of Knowledge Management in SMEs – Utz Fehlau). Even in larger companies, if performance metrics and deadlines leave no room for reflection, employees won’t prioritize writing reports or holding lessons-learned meetings. Likewise, a lack of budget for knowledge initiatives (like training sessions or communities of practice) sends a message that the organization doesn’t truly value knowledge transfer. Overcoming this requires leadership to integrate knowledge-sharing into job expectations and allocate dedicated resources (time, tools, personnel) to support it – treating it as a necessity, not a luxury.

Finally, resistance to change can be a significant hurdle. Implementing knowledge transfer practices often requires changing habits – adopting new tools, documenting more information, or collaborating more openly. If the organizational culture is set in its ways, employees (and even managers) may be reluctant to embrace these changes. For example, introducing a new wiki or collaboration platform might be met with “why should I use this?” and go underutilized. Frequent organizational changes (like restructurings or high turnover) can further disrupt knowledge flows and trust (The Importance of a Knowledge Sharing Culture (2025)). To address resistance, companies must manage change carefully: communicate the benefits of sharing knowledge, provide training and support for new systems, and lead by example. When employees see leaders actively participating in knowledge sharing, it signals that openness is valued. Over time, building a strong learning culture and rewarding knowledge-sharing behaviors will chip away at structural and cultural obstacles to knowledge transfer.

5. Knowledge Transfer in Specific Organizational Contexts

5.1 SMEs

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face unique knowledge transfer challenges. Often, critical know-how in an SME is concentrated in a few key people. If an experienced employee leaves, they may take years of tacit knowledge with them (The Strategic Importance of Knowledge Management in SMEs – Utz Fehlau). SMEs also rely heavily on informal communication – much knowledge sharing happens organically through daily interactions rather than formal systems. While effective in a tight-knit team, this informality becomes risky as the company grows or new employees join who weren’t part of those original conversations. Additionally, SMEs have limited resources for formal knowledge management, so adopting complex KM software or extensive documentation processes is often not feasible. Instead, SMEs benefit from simple, low-cost practices: creating basic checklists or how-to guides for key processes, pairing junior staff with veterans for on-the-job mentoring, and using lightweight tools (like a shared drive or internal wiki) to record important information. The aim is to capture and share essential knowledge in a sustainable way without overburdening a small team. By building a habit of documenting and exchanging know-how early, SMEs reduce the risk of knowledge loss as they expand.

5.2 Large organizations

Large enterprises have more resources for knowledge programs, but their scale and complexity introduce challenges. In a big company, valuable insights can be scattered across departments and regions, making it difficult for one part of the organization to know what another part has learned. To address this, large firms often implement formal knowledge management initiatives (enterprise knowledge portals, internal knowledge bases, etc.) and may dedicate staff or departments to KM. These structures help systematically capture and distribute information. However, large organizations frequently struggle with organizational silos – divisions or teams that don’t share information with each other. Overcoming silos requires strong leadership support and incentives for cross-unit collaboration. Another issue is user adoption of knowledge systems: deploying a sophisticated knowledge repository is of little use if employees don’t use it. Long-standing habits or skepticism can result in minimal participation, so change management is critical (for example, actively encouraging and rewarding contributions to the knowledge base). In summary, while large organizations tend to have formal tools and processes for knowledge transfer, they must actively work to break silos and foster a sharing culture. Even the best technology will not deliver results if people aren’t motivated to share and seek out knowledge across the enterprise.

6. Measuring the Effectiveness of Knowledge Transfer

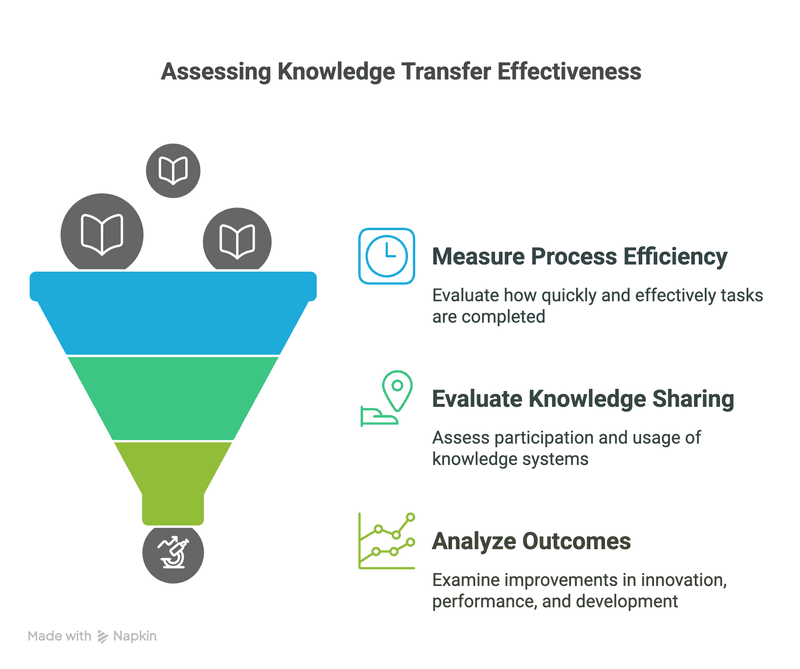

To gauge whether knowledge transfer efforts are working, organizations track several types of metrics. One focus is process efficiency and reuse. For example, if knowledge is flowing well, teams should solve problems faster and avoid redundant work. Metrics like the time taken to find needed information or the frequency of repeated mistakes can indicate improvements. A drop in project rework or a faster turnaround on customer queries, for instance, suggests that people are leveraging existing knowledge instead of starting from scratch. Another set of measures looks at knowledge sharing activity. This includes usage statistics of knowledge systems and participation rates. Companies track things like how often employees search the knowledge base, contribute to a wiki, or ask/answer questions on internal forums. High usage and contribution rates – and positive feedback about the ease of finding information (Knowledge Sharing Metrics To Determine ROI – Bloomfire) – signal that knowledge transfer tools are being adopted effectively.

Beyond process metrics, organizations examine outcomes that knowledge transfer is meant to drive. Innovation is one: a boost in new ideas, patents, or product improvements can be tied back to better knowledge exchange enabling creative combinations of expertise. Operational performance is another: if departments that implemented knowledge-sharing initiatives show improved KPIs (for example, shorter training times for new hires or higher customer satisfaction due to quicker issue resolution), that’s strong evidence of effective knowledge transfer. Even employee development can be a gauge – for instance, faster onboarding (reducing time for a new hire to become fully productive) suggests that training and mentoring are successfully transferring needed knowledge. In summary, by looking at how readily employees can access and use knowledge (efficiency and usage metrics) and the resulting improvements in innovation, responsiveness, and competency, organizations can assess the real impact of their knowledge transfer efforts.

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

Knowledge has clearly become a strategic asset, and effective knowledge transfer is essential for organizations to learn, innovate, and stay competitive. A successful approach to knowledge transfer is inherently multi-faceted: it requires people-focused initiatives (to foster a sharing culture and exchange tacit know-how), the right technology (to capture and disseminate information efficiently), and process discipline (to systematically learn from successes and failures) – all supported by a strong culture of learning and leadership commitment. Companies that align these elements will be best positioned to leverage their collective knowledge as a strategic advantage.

Looking ahead, digital transformation and AI will continue to reshape how knowledge is shared. The rise of remote and hybrid work means organizations must enable knowledge exchange even when colleagues are not face-to-face – which elevates the importance of robust digital collaboration platforms and accessible knowledge bases. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence offers new opportunities to enhance knowledge transfer. For example, AI-powered search and chatbots can help employees find information or expertise more quickly, and future tools may assist in capturing tacit knowledge through natural language interfaces. However, even as these technologies advance, the human element remains critical. Organizations will need to maintain trust, engagement, and clear incentives for people to contribute and use knowledge. The future likely lies in a human-AI partnership in knowledge management: machines accelerating knowledge discovery and answers, while humans provide the context, creativity, and collaborative spirit that turn information into innovation. By embracing that combination, organizations can ensure their hard-earned knowledge remains a renewable source of value in the digital age.